HunsEmpire

The Huns (408 to 453)

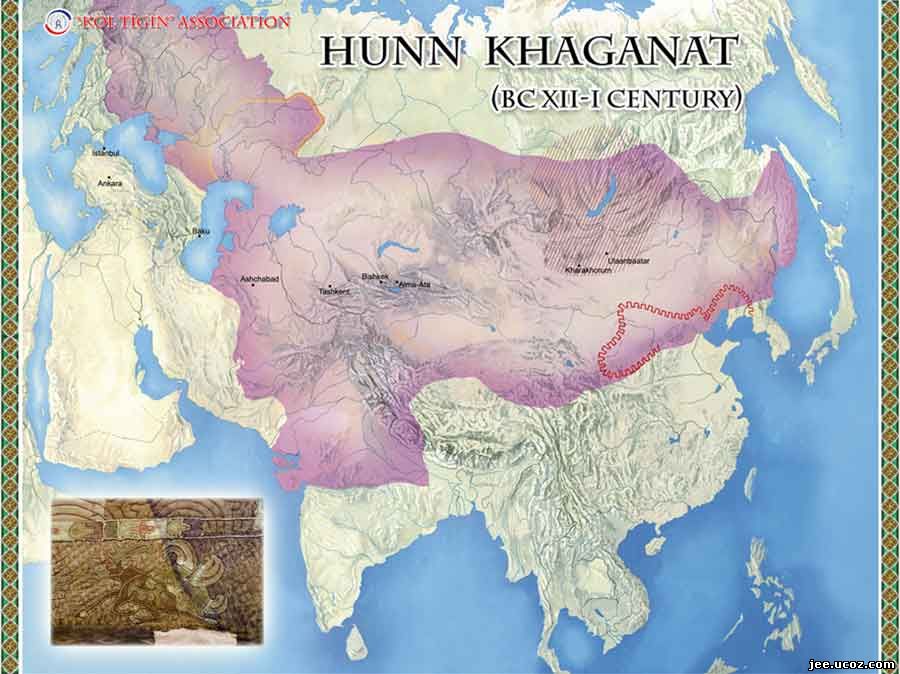

The Huns were a nomadic people from around Mongolia in Central Asia that began migrating toward the west in the third century, probably due to climatic change. They were a horse people and very adept at mounted warfare, both with spears and bows. Moving with their families and great herds of horses and domesticated animals they migrated in search of new grasslands to settle. Due to their military prowess and discipline, they proved unstoppable, displacing all in their path. They set in motion a tide of migration before them as other peoples moved to get out of their way. This domino effect of large populations passed around the hard nut of Constantinople and the Eastern Roman Empire to spill over the Danube and Rhine Rivers, and ultimately overwhelm the Western Roman Empire by 476.

Finding lands to their liking, the Huns settled on the Hungarian plain in Eastern Europe, making their headquarters at the city of Szeged on the Tisza River. They needed large expanses of grasslands to provide forage for their horses and other animals. From this area of plains the Huns controlled through alliance or conquest an empire eventually stretching from the Ural Mountains in Russia to the Rhône River in France.

The Huns were superb horsemen, trained from childhood, and some believe they invented the stirrup, critical for increasing the fighting power of a mounted man charging with a couched lance. They inspired terror in enemies due to the speed at which they could move, changing ponies several times a day to maintain their advance. A second advantage was their recurved composite bow, far superior to anything used in the West. Standing in their stirrups, they could fire forward, to the sides, and to the rear. Their tactics featured surprise, lightning attacks, and the ensuing terror. They were an army of light cavalry and their political structure required a strong leader to hold them to a purpose.

The peak of Hun power came during the rule of Attila, who became a leader of the Huns in 433 and began a series of raids into south Russia and Persia. He then turned his attention to the Balkans, causing sufficient terror and havoc on two major raids to be bribed to leave. In 450 he turned to the Western Empire, crossing the Rhine north of Mainz with perhaps 100,000 warriors. Advancing on a front of 100 miles, he sacked most of the towns in what is now northern France. The Roman general Aetius raised a Gallo-Roman army and advanced against Attila, who was besieging the city of Orleans. At the major battle of Chalôns, Attila was defeated, though not destroyed.

The defeat at Chalôns is considered one of the decisive battles of history, one that could have meant collapse of the Christian religion in Western Europe and perhaps domination of the area by Asian peoples.

Attila then invaded Italy, seeking new plunder. As he passed into Italy, refugees escaped to the islands off the coast, founding, according to tradition, the city of Venice. Though Roman forces were depleted and their main army still in Gaul, the Huns were weak as well, depleted by incessant campaigns, disease, and famine in Italy. At a momentous meeting with Pope Leo I, Attila agreed to withdraw.

The Hun empire disintegrated following the death of Attila in 453 with no strong leader of his ability to hold it together. Subject peoples revolted and factions within their group fought each other for dominance. They eventually disappeared under a tide of new invaders, such as the Avars, and disappeared from history.

The Huns (408 to 453)